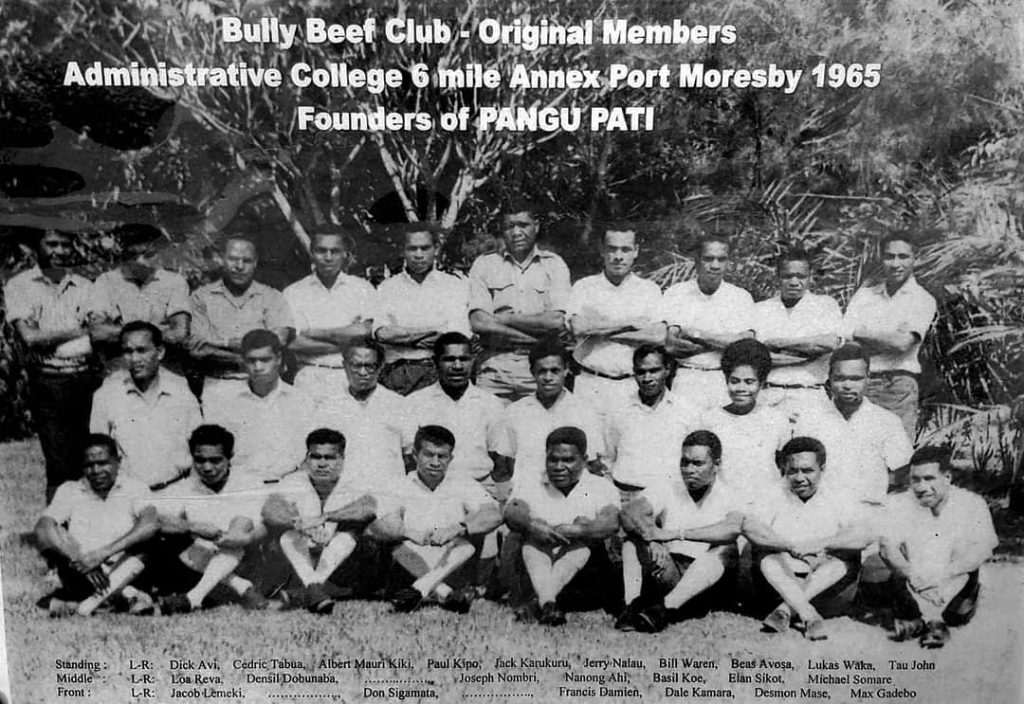

Bully Beef Club - Original Members Administrative College 6 Mile Annex Port Moresby 1965. Founders of PANGU PATI

The story of the Bully Beef Club begins in the classrooms, dormitories and student homes of Port Moresby’s Administrative College in the 1960s. Here, young Papua New Guineans debated nationalism, justice, and the future of their country. What began as informal late-night discussions over tins of beef would grow into a movement that shaped the path to independence. Today, the Australian Government is supporting the Somare Institute of Leadership and Governance (SILAG)—the successor to the Administrative College—to develop a timeline and resource that captures the Club’s legacy. This project honours the young men and women who transformed everyday frustrations into political action and built the foundations of a new nation.

In the mid-1960s, a handful of young men and women in Port Moresby would gather late into the night over tins of corned beef. They argued about justice, equality, and the future of Papua New Guinea. What began as late-night student debates became known as the Bully Beef Club — the crucible of a political generation that would lead the country to independence.

The Administrative College, where many of these students studied, was meant to train Papua New Guineans for middle-level posts in the colonial service. Instead, it became a breeding ground for politics. Students frustrated by poor housing, meagre food, and unequal salaries compared to their expatriate peers began to see their grievances not as isolated problems but as signs of a deeper injustice.

Future leaders like Michael Somare, Albert Maori Kiki, John Kaputin, Ebia Olewale, Gavera Rea, and Joseph Nombri were at the centre of these conversations. Their friendships and debates formed a network of solidarity that would shape the nation’s destiny.

Brian Jinks interview on training facilities

Source: Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Brian Jinks interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2008, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/12.

Description

Brian Jinks was one of the early Australian lecturers at the Administrative College in Port Moresby. He encouraged open discussion, challenged his students to think critically, and helped nurture the spirit of independence that was beginning to take hold across the campus.

Jinks reflects on the shortcomings of Australian colonial training schemes in the 1960s. He recalls the poorly designed Finschhafen training centre, where students had little structure, few resources, and lived in makeshift conditions. After bluntly telling senior officials it was “a waste of space,” the centre was shut down, with training redirected to the Administrative College. His experiences with cadet officers reinforced his frustrations: courses were outdated, living arrangements chaotic, and discipline undermined by heavy drinking. To Jinks, these failures highlighted the complacency and lack of imagination within the administration, even as figures like David Chenoweth and institutions like ADCOL sought more serious reform and localisation.

Brian Jinks

… two courses. No, perhaps only one. I think mine was only the third course.

Jonathan Ritchie

And how long was the course?

Brian Jinks

Well, it lasted like an academic year. Okay, yeah. I can't... Yeah, look, it was basically like an academic year with these patrol interludes. I think there were only about three patrol interludes all told. There wasn't a hell of a lot. And these guys used to live down there and they did their own cooking and washing and all that sort of stuff. And there weren't any other resources. We organised the occasional cricket game or some cricket match with the Dregger Half [Dregerhafen Teachers College] and Teachers College and things like that. But we had them around to our place a couple of times for afternoon tea and so on. [We] invited some of the Europeans on the station and everybody sat in stunned disbelief and, oh God, it was just, it was incredible. By and large, they were a nice bunch of guys, nothing about it, and most of them went some distance. But it was, I mean, another example, for one reason or another, absolute total incompetence. Whoever had designed, there was no design, there was no carry through, there was nothing.

Anyway, at the end of the, Rhonda left, I decided that I was going to do my Honors. Don Rawson, academics, not a bad idea. Yes, please. Oh, in the meantime, I'd applied to become registrar of the administrative college. Mainly because I wanted, you know, looking for something or another out, but also more in a training area or something. And I was interviewed by David Chenoweth. Have any of you ever heard of David Chenoweth? (Jon Ritchie) “I have.” David, and he said, “look, you don't want to be registrar, finish your Honors degree and come back as a lecturer.” Yes, sir. So in 65, I took leave without pay most of the year, I think. And that's when I did my Honors year. And now what was the point? That's right. Rhonda left a bit early, and I was bumming, I was filling in time until the beginning of the academic year because I didn't want to have to spend any more time without salary than I had to. I was actually waiting for the, my successor actually was Graham Hogg who'd been the guy in the next bed to me, a really nice guy. Anyway.

Jonathan Ritchie

Back in Port Moresby.

Brian Jinks

Yeah, back in Moresby as a cadet. So Graham turns up. But at the end of the year, there was a presentation ceremony, and I think J.K. McCarthy came over. I'm pretty sure J.K. was there, but Harry West. I'm sure you've heard or know of Harry. Harry West was the assistant director for some bloody thing or another, whatever. And I organized a spread and everything, and Harry said to me, “Where did all this come from?” And I said, “it's, we paid for it. I bought lots of eggs and the boys, boys, I caught, the students, boiled them up in the kitchen” and I didn't know how to boil eggs. We had all these smashed boil eggs. Really funny. But the women on the station helped and they, the European women on the station, we had a spread. Harry said, “who's going to pay for it?” He said, “we're not staying overnight. I can't write you a medical. I can write you out an accommodation warrant for lunch, but that's not going to cover much”. And I said, “Look, Harry, get on the plane, go back to Moresby and close this place down. It's a waste of space. It's doing absolutely nothing.” By that time I'd been to see the Administrative College, I said, “All of this can be done at the Administrative College and done better.” Not that I, I mean, at that stage, the Administrative College was only at the ex-Crewalk's house down at Six Mile. I don't know whether, it wasn't at Waigani. It was at Six Mile. It was just a two-story house that belonged to the Creewalts. The “Creewalts” [Creed & Woolt Ltd], you remember the Creewalts department store in Moresby? No, before your time. Anyway, it was a big one.

So that was the administrative college. In fact, the headquarters at David’s office was still in Konedobu by that stage. Anyway, but I said, look, they can do it better there. And they'd already had people like Michael Somare and so on, and Albert Maori Kiki and so on, of course, was there. So the Finschhafen Training Centre was closed down, bang, because it was absolutely useless. Or at least it never functioned again. And Graham became ADO Finschhafen, he took over. And that was the end of the staffing and everything. But that was another, to me, that was another example of absolute incompetence. I went down, did the Honors year, and then in '66 went, oh, actually I was appointed in the meantime, I was appointed district officer training in headquarters. And I did one cadet's course. One group of cadets arrived on the plane the day after I got back. And I was staying in, what's that place on Ella Beach, Kermadec? [Kermadec Hostel] The senior officer, no, the senior officer's quarters. Oh, that's probably, that probably doesn't exist anymore either. Anyway, it's just above Ella Beach School there, somewhere up on the hill a bit. I was staying there.

Jonathan Ritchie

Churches or...

Brian Jinks

Yeah, whatever. Rhonda hadn't come back. Well, there was no house for us. The houses at Waigani weren't ready. And I'd put in for this position, or I was promoted to the position or whatever, but I was waiting for that to be confirmed, so I had this course of cadets. And they arrived on the plane and I met them and I thought, God, deja vu. And the course that they had was no better, basically, than the one that I'd been through 10 years earlier. They were in, they were out at Konedobu in a classroom that was scarcely better. I gave them, there must have been some kind of a structure for the course because there were a lot of other people doing bits and pieces. There had been a district officer training for some time, so at least the thing had a bit more of a framework than it had, but the cadets were still put up in, well they were now put up in pubs, they didn't have to live in a tin shed. They were living in the bottom pub and the top pub. I would remember going around to see them. But there was nothing I could do to organise any function. There was nowhere to organise a function apart from a booze up somewhere. There was no structure for them for after hours. And of course, by that stage, it was multiracial grogging, and there was a lot of boozing. Because they're right in the middle of town, and da da da da da, and I thought, what the, you know, what are we gonna do about this? And they did, they went out on canoes, one of them got so badly sunburned on his feet that he couldn't walk, he had to finish up in the hospital and I, you know, it was just, I thought to God, you know, can't we do it any better than this? (Jonathan Ritchie) “So you had", there were all sorts of things that I could have told them, but as I can recall, I wasn't scheduled into the thing, not that I particularly wanted to be in it, I suppose, as I can't remember, because I think my mind was well and truly, truly on the administrative college by that stage. But, you know, I thought, this is just, it's crazy, you know, it's just, where is this field? Why haven't they adopted the Finschhafen model? I can remember talking about this, you know. You had this thing at Finschhafen, and the model was fine, the resources stank. You've got the, Moresby's not the place, I remember saying, Moresby is not the place for this sort of thing. Have it somewhere else, you know, where you can get the people together and after hours and all this sort of stuff and so on, but anyway. But you see that required money and imagination, but people, see there was this lack of, there was this level of complacency all the time. She'll be right, she'll be right. It's okay. And of course it had worked in the past because people put up with it.

Jonathan Ritchie

People's goodwill. Pardon? Relying on people's goodwill, I suppose.

Brian Jinks

Self-interest. Self-interest. I mean, the reason why you're in Papua New Guinea because the money was good and the conditions were good and the leave was generous. And I'm not saying everybody was like that, but you know, I think that's a, that's a pretty fair sort of an estimate. It was an easy life, really. You know, if you were on a, if you, as I said, the archetypal Kiap in charge was a guy who married kids, da da da da da, not much ambition. And then as the years went on and he heard about this crazy thing called independence and so on. Oh, I'll hang on here, you know. I was quite, yeah. See, I could have stayed on at Sydney University. God, I'm glad I didn't. But I thought, no, no, no, there's a golden handshake back there. I must say I was bored rigid already after two years of, in those days, of course, there were only day lectures too. But the classes were so big, I used to have to do an 11 o'clock on the table.

The Spark of Change

The Club’s gatherings were informal — often held in cramped dormitories or at Albert Maori Kiki’s house in Hohola, where his wife Elizabeth would cook for the hungry students. Somare later remembered:

“We develop into a small club that we used to call it Bully Beef Club. We talked politics and how countries would be governed. And that made me take interest in politics.”[1]

These conversations gave students confidence to challenge the colonial administration directly. They wrote letters, staged deputations, and pressed for equal pay. At the same time, they began meeting with members of the House of Assembly, absorbing lessons in parliamentary politics and dreaming of a future where Papua New Guineans would govern themselves.

[1] Courtesy of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Michael Somare, interview on Monday Conference, 1972.

Somare Remembers the Bully Beef Club

Source: ABC_MondayConference_Somare_proxy_ada44b7

Media & Visuals (placeholders)

Description

Reflecting on his student years, Michael Somare recalls how informal conversations at the Administrative College grew into what became known as the Bully Beef Club. A handful of like-minded young men—including future minister Albert Maori Kiki—shared ideas about politics, governance, and Papua New Guinea’s future. Somare explains that by speaking with one voice, they could be heard more clearly than as individuals. These late-night gatherings, fuelled by shared tins of corned beef, became a crucible for political debate and solidarity. For Somare, the club was decisive: it sparked his interest in politics and helped nurture the leadership that would guide the nation to independence.

Michael Somare

And while studying for my matriculation, I found that there are a group of people, I think 3 or 4, who are now in my ministry.

We had same ideas and same thoughts about the place.

We thought, you know, with one voice you could, you could be heard much more than ordinary individual trying to say something.

And we develop into a small club that we used to call it Bully beef club, Bully beef club, Bully beef club.

For those who have read 1000 Years in Lifetime by Albert Murakiki, who is now my minister for lands would follow what had happened during those days.

And we we've been we talk politics and we talk about, you know, how countries would be governed and so on.

And that made me take interest in politics.

The Club That Built a Party, The Party That Built a Nation

The Bully Beef Club was never an official organisation. Its “membership” was fluid, and its name only came later. But its significance was undeniable. Out of those debates came the foundation of Papua New Guinea’s first major political party, the Pangu Pati, in 1967. Just eight years later, in 1975, the country achieved independence.

The story of the Bully Beef Club reminds us that big changes often begin in small rooms, with a few committed voices, a shared meal, and the courage to imagine a different future.

Ted Wolfers on Students, Pangu, and Early Political Alliances

Source: Courtesy of the National Library of Australia. Edward (Ted) Wolfers interviewed by Jon Ritchie, 2009, Australians in Papua New Guinea (PNG) 1942–1975 oral history project, ORAL TRC 5920/33.

Description

Ted Wolfers was an Australian lecturer and scholar who guided young Papua New Guineans, linking education, justice, and the path to independence.

Wolfers recalls tensions in the mid-1960s between students and national politicians. Many students were sceptical of their leaders’ literacy and independence credentials and deeply frustrated by issues like local pay scales. Wolfers himself built friendships during this period with figures such as Barry Holloway and Tony Voutas, Australian expatriates who became close allies of emerging Papua New Guinean nationalists like Michael Somare and Albert Maori Kiki. He recounts Holloway’s unusual generosity in lending his battered car to students at ADCOL, symbolising trust and solidarity. While Wolfers was not directly involved in the formation of the Pangu Pati in 1967, he observed its emergence closely, recognising it as part of the global tide of decolonisation. Reflecting later, he notes that independence felt inevitable in principle but uncertain in timing, with crises in Bougainville and East New Britain eventually proving pivotal.

Jonathan Ritchie

Can I just stop you there? So the students were quite anti some of the national politicians. Why were they?

Ted Wolfers

I'm trying to remember the details of it. I think in some cases they thought they weren't critical enough of what was going on. They were a bit condescending about the degree of literacy and so on. I don't remember the details of it, to be honest. I think they certainly didn't like what they saw as this patriot domination of the legislature.

Jonathan Ritchie

But then they met these guys.

Ted Wolfers

And they met some of these guys. I know some of them knew each other anyway, they didn't need me, but we did try to... It just seemed to me it was getting a bit unhealthy, and the students were very upset about things like local pay scales and the economic rentals and so on. But I think they also thought these guys were not the ones who were going to lead the country at independence. They were not very optimistic about the degrees of literacy and education and so on. But that's when I met Barry [Holloway]. And then Barry said, and this was '65, he said, when you come to the Highlands, look me up. And when I did this trip to meet the external students, I went to Lae, and Barry came down and picked me up and took me up to Kainantu. And that became a pretty, well, it's been a lifetime friendship too.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, yes.

Ted Wolfers

And it was through Barry, I think, that I met Tony Voutas, but only after Tony had been elected. And then I think, yeah, then we did a drive together. What year was that? Probably '67, '68. I'm not sure now. We did a drive somehow. Tony Voutas came up to the Highlands and Holloway and Voutas and I drove from there down to Bulolo and to Mooming [editor note: unsure]. And that began another friendship, which has been over a long time. But I mean, those were the guys who became, the people who became, if you like, the Australian, the then Australian allies of the Papua New Guinea nationalists.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, yes.

Ted Wolfers

They were the ones who then forged the friendships with Somare and Murray Kiki.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes. And they were in at the ground floor at the beginning of Pangu, weren't they?

Ted Wolfers

Yes. I mean, Holloway was. Holloway did some very unusual things. I'm trying to remember, it was '67, yes it was, when he came out to ADCOL and he was trying to help me with his go-between role and he had to go back to the Highlands, and he had this little black car. I can't remember what it was, it was a bomb, he didn't even need a key to start it, but he left it with the students to use, and so they had a car to use. So he was, in a sense, he was being very generous, in a, I suppose a modest way, but in those days quite remarkable, because nobody else had cars out there. You know, [it] began some of those linkages too, causing me to remember a lot of things now. But yeah, there was this little bomb and so they would have a car to go into town if they needed to or go out on a Friday night.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, yes.

Ted Wolfers

And he was unusual in that sense that I think he understood, and Voutas most certainly did, that independence was coming. that it was going to be led by Papua New Guineans and it was very important. You know, they saw their role as being in some way linked to all that. So they're pretty unusual people for that time.

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes, yes. So when did you first hear about Pangu?

Ted Wolfers

I think I'm correct in saying I was out of the country that I came a few weeks after all of that. That it was full, I certainly wasn't, I wasn't surprised by it. I certainly wasn't part of it.

Jonathan Ritchie

You weren't part of it.

Ted Wolfers

No. I mean, in one sense, were a lot of those my friends and linkages, yes. But was I involved in the formation of Pangu? No. I think I'm correct. It was early in 1967, wasn't it? No, I was in Australia reorganizing my life to go up there with the Institute. Did I think political parties were going to be important? Yes, because when the New Guinea United National Party, I think it was called, was formed by Oala Oala-Rarua, a lot of us went into those meetings not to be part of it, but to observe it and to understand it, and I certainly went to them. I remember all the spooks sitting there taking their notes and that's all a matter of record so in one sense I knew it but um no I wasn't directly involved in that, Cecil Abel was …

Jonathan Ritchie

Yes okay, yes. So with the Fellowship you were there you said it until 70 or you said late 71… 71 yes, and in that time, what you were really, you had to write your monthly newsletter, and where were you working? Did you have an office?

Ted Wolfers

No, I had no official affiliations with anything, so I lived in my house in Hohola, and I would have these long empty days trying to write. I spent a lot of time out in the New Guinea collection at the University of Papua New Guinea, which is why some people think, I've met people who actually think taught them at the university. It's amazing. I mean, I was around the university, but it was only using the library. At one point when my PhD really didn't seem it was going to happen in Sydney, I enrolled for a Masters at UPNG, but that also wasn't going to happen. But I used to spend days and days, and they were marvelous. They gave me access to the stacks. That's where I found stuff that I didn't know existed and learned a lot. And that's what allowed me to do things like writing about language and writing about mathematics and all sorts of weird things because I had access to this extraordinary collection of materials and also of course the New Guinea Research Unit and they for a period gave me an office out there which meant I'd go out there and meet other academics and I would also use their library facilities, which were very good. So that gave me a kind of place to, I'm just trying to remember exactly, I can't remember the exact years of that, but it meant, you know, I was, I did get out of the house sometimes, it was a good way of writing and not be locked in all day. And I met a lot of very interesting academics and did a lot of reading out there too.

Jonathan Ritchie

I asked a question earlier about Ulli Bayer and of course I think you mentioned that he'd read your work.

Ted Wolfers

Well, he said — I think he said to me — that before he came out he’d been trying to find out, I think I’m quoting him, he’d been trying to read about Papua New Guinea, and all he could get was my newsletters. I knew his work because there was The Penguin Book of Modern African Poetry that he did with Gerald Moore, and so when UPNG recruited him, I thought they’d made quite a catch, because that book certainly inspired me a lot.

Jonathan Ritchie

And you also mentioned Sir Vincent Eri, and of course he was part of that whole creative group.

Ted Wolfers

Yes, but that was all a bit later, but I was lucky in that period that when Ulli [Bayer] did come and he started I mean I'm trying to remember I think the connection between us was actually that Albert [Maori Kiki] had met him and so we used to get invited a fair bit to … and again that was another place you met a lot of those people. But I mean, he was doing his, I wasn't involved in what he was doing in getting people to write novels and stuff.

Jonathan Ritchie

But you have a sense, I have a sense, listening to you and others, of the sort of ferment that must have been going on at that time in the late 60s.

Ted Wolfers

Well, it was an exciting period, in a way, because you, I mean, if you looked around the world, there weren't, you know, decolonisation seemed to be inevitable, the prospects were a bit worrying in different parts of the world, or sorry, the comparisons of other parts of the world made the prospects a bit worrying. But yeah, and I mean the university was a very exciting place in that sense. Firstly, I think they recruited quite outstanding academics in those days. It was an exciting place to go by then. It hadn't been quite the same that when I first went there, but with the university and so on. Somehow there was a sense of adventure. If you look at the subsequent careers of many of the Australian academics who went there, they really had quite stellar careers afterwards because I suspect they, I suspect, they probably got their senior positions, their chairs, and so on a couple of years earlier than they might have in Australia, but that was a good thing, because they then got excited, then they went, most of them went back. And it was an exciting place to be, and you met a lot of very interesting people.

Jonathan Ritchie

I think you've already mentioned this and certainly alluded to it, but of course the decolonisation, which was just around the corner, had already happened in large parts of the world elsewhere. So there was some sense of, was there? Some sense of where the final stage in this?

Ted Wolfers

Well, I think the point is that had you, I probably would have given you a different answer at different points in time, that at the time of the first House of Assembly, when I was first reading about decolonisation, I would have given you one prediction. There was a period in '68, '69 where I couldn't see how it was going to happen. There's nothing much going on. It was hard to see how decolonization was going to occur. Then you got the confrontations on the Gazelle and Bougainville, and it didn't seem to be going the way you might otherwise have expected. So in one sense, there were periods where it was always inevitable, I suppose, if you'd read what I'd read and thought what I thought, but it was hard to see how it was going to go or when it was going to happen and what the trigger would be. And I think that's where the events in East New Britain and in …